The 4 C’s

The Four C’s – An Important Tool For Families

Sometimes little slogans can help us remember important recovery topics. The 4 C’s is one of them: Family didn’t cause mental illness or addiction, can’t control it, can’t cure it but certainly can cope with it.

You didn’t cause it

This is something that a lot of family members, especially parents, wonder about. We ask, “Is it my fault? Was I too strict, or neglectful, or permissive, or busy? If we had seen the signs earlier, could we have caught the problem before it got out of hand? My father had bipolar disorder, should I even have had children knowing they could get it? What about the time I yelled at her for not doing the dishes?” The questions go on and on, and they can trouble us for years. It’s interesting that most researchers are not nearly as preoccupied with these questions as families are. For example, a search of a research database, EBSCO, for causes (“etiology”) of mental illness in general, as well as schizophrenia, bipolar and depression, showed 670 results for the years 2015-2018, but only 7 of them mention parental involvement, most of them just in passing. Now you might say, “I’m the parent, how could I not have had something to do with these problems?” Of course, when people live together, they always influence each other. But that’s a far cry from causing the mental illness or addiction. You didn’t cause it, just like you didn’t cause their last cold. And don’t forget all the good you have contributed to your loved one!

You can’t control it

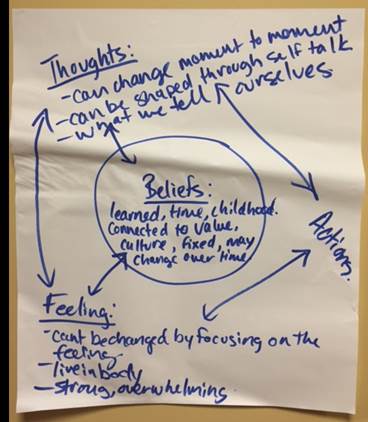

Let’s start with the “you” part of the sentence. Maybe there’s a little bit of control or help that the person with the mental illness can exert, maybe their care providers can – but you certainly can’t. You can’t change what’s happening in your loved one’s brain chemistry. You can’t make someone feel or think differently. You can’t stop the cravings. Can you have some influence? Yes, quite possibly. If your loved one is open to it, you can share your thoughts and experiences. Telling your loved one what to do rarely works, even when you are absolutely certain that it will have good results. Paradoxically, giving up the idea that you can have any control over this can increase the connection and therefore influence you have with your loved one. A lot of this is discussed in Dr. Amador’s book, “I’m not sick, I don’t need help.”

You can’t cure it

The idea of cure in mental illness and addiction is controversial at best. Many people would say you can’t cure it. But – and here is the good news – a person can be in recovery and manage it. There are many people who can manage it so well that the problems associated with mental health and/or addiction hardly ever crop up again. Be that as it may – you are not the person that needs to work on their recovery and management of the problem. That’s your loved one’s job, with the help of their health care providers. What you can do is ask your loved one how they want to be supported (go back to Dr. Amador’s book for ideas on how to do that).

You can cope

What you can do is to work on your own recovery. What do you need to do to be in a better place? When you are more relaxed, less stressed, less worried, you can lend better support to your loved one. Some time ago, we talked about coping in our support group. We asked the question, “What helpful things do you often do when you first encounter a problem?” We collected a few ideas, noting that we often tend to use different approaches for different situations and when different people are involved. For example

- slow down (also slow down thoughts)

- learn more about the issue/person before facing the problem

- observe the situation, without necessarily doing anything about it

- step back (“rather than shooting from the hip”)

- take one thing at a time

- take time out

- try to figure out what’s going on

- use techniques learned from Xavier Amador’s book “I’m not sick, I don’t need help”

- ask: how can i help?

- break down the problem in to manageable bits

- exercise

- distract yourself with other things, (e.g. housework)

- take notes of what happened

Our newsletter often talks about coping ideas. These may be of special interest:

- March 2021 – Communication

- December 2018 – Coping

- February 2017– Change

- December 2016– Reflection

- September 2016– Communication

- July/August 2016– Spirituality

- June 2016– Family Strengths!

- January 2016– New Beginnings

- December 2015– Self Care during the Holidays

- November 2015– National Family Caregiver Week

- September 2015– Addiction

- June 2015– Mental health Apps

- March 2015– Special Edition: Addiction

- January 2015 – (Includes an article on recovery and goals)

- October 2014– Special Edition: Financial Matters

- July 2014– (Contains the article “Re-empowering family members disempowered by addiction”

- March 2014– (Contains an article about boundaries)